Ebola virus

also Ebola hemorrhagic fever, or EHF), or simply Ebola, is a disease of humans and other primates caused by ebolaviruses. Signs and symptoms typically start between two days and three weeks after contracting the virus as a fever, sore throat, muscle pain, and headaches. Then, vomiting, diarrhea and rash usually follow, along with decreased function of the liver and kidneys. At this time some people begin to bleed both internally and externally.

The disease has a high risk of death, killing between 25 percent and 90

percent of those infected with the virus, averaging out at 50 percent. This is often due to low blood pressure from fluid loss, and typically follows six to sixteen days after symptoms appear

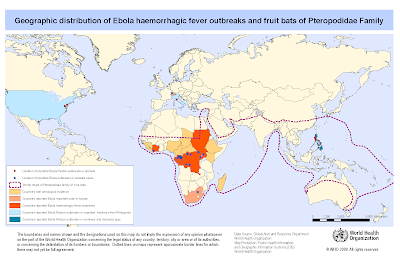

The virus spreads by direct contact with blood or other body fluids of an infected human or other animal. Infection with the virus may also occur by direct contact with a recently contaminated item or surface. Spread of the disease through the air has not been documented in the natural environment. The virus may be spread by semen or breast milk for several weeks to months after recovery. African fruit bats are believed to be the normal carrier in nature, able to spread the virus without being affected by it. Humans become infected by contact with the bats or with a living or dead animal that has been infected by bats. After human infection occurs, the disease may also spread between people. Other diseases such as malaria, cholera, typhoid fever, meningitis and other viral hemorrhagic fevers may resemble EVD. Blood samples are tested for viral RNA, viral antibodies or for the virus itself to confirm the diagnosis.

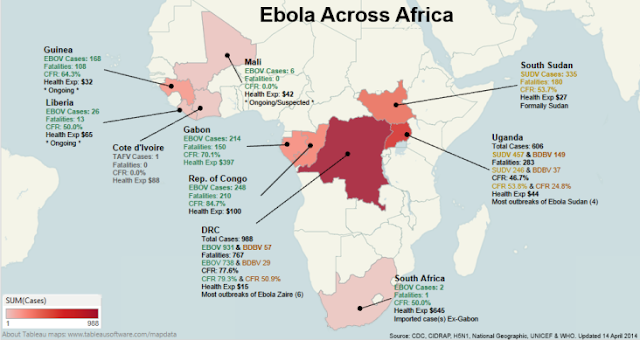

No specific treatment or vaccine for the virus is commercially available. Efforts to help those who are infected are supportive; they include either oral rehydration therapy (drinking slightly sweetened and salty water) or giving intravenous fluids as well as treating symptoms. This supportive care improves outcomes. EVD was first identified in 1976 in an area of Sudan (now part of South Sudan), and in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The disease typically occurs in outbreaks in tropical regions of sub-Saharan Africa. Through 2013, the World Health Organization reported a total of 1,716 cases in 24 outbreaks. The largest outbreak to date is the ongoing epidemic in West Africa, which is centered in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia. As of 9 November 2014, this outbreak has 14,098 reported cases resulting in 5,489 deaths.

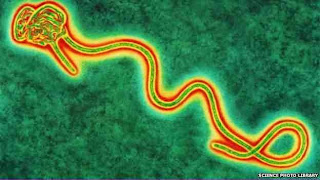

Ebola virus (EBOV, formerly designated Zaire ebolavirus) is one of five known viruses within the genus Ebolavirus. Four of the five known ebolaviruses, including EBOV, cause a severe and often fatal hemorrhagic fever in humans and other mammals, known as Ebola virus disease (EVD). Ebola virus has caused the majority of human deaths from EVD, and is the cause of the 2013–2014 Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa, which has resulted in at least 14,098 suspected cases and 5,489 confirmed deaths.

Ebola virus and its genus were both originally named for Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), the country where it was first described, and was at first suspected to be a new "strain" of the closely related Marburg virus. The virus was renamed "Ebola virus" in 2010 to avoid confusion. Ebola virus is the single member of the species Zaire ebolavirus, which is the type species for the genus Ebolavirus, family Filoviridae, order Mononegavirales. The natural reservoir of Ebola virus is believed to be bats, particularly fruit bats, and it is primarily transmitted between humans and from animals to humans through body fluids.

History and nomenclature

Ebola virus (/ε'boʊlə vaɪrəs/) was first identified as a possible new "strain" of Marburg virus in 1976. At the same time, a third team introduced the name "Ebola virus", derived from the Ebola River where the 1976 outbreak occurred. The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) identifies Ebola virus as species Zaire ebolavirus, which is included into the genus Ebolavirus, family Filoviridae, order Mononegavirales. The name "Ebola virus" is derived from the Ebola River—a river that was at first thought to be in close proximity to the area in Democratic Republic of Congo, previously called Zaire, where the 1976 Zaire Ebola virus outbreak occurred—and the taxonomic suffix virus.

In 2000, the virus name was changed to Zaire Ebola virus, and in 2002 to species Zaire ebolavirus. However, most scientific articles continued to refer to "Ebola virus" or used the terms Ebola virus and Zaire ebolavirus in parallel. Consequently, in 2010, a group of researchers recommended that the name "Ebola virus" be adopted for a subclassification within the species Zaire ebolavirus, with the corresponding abbreviation EBOV. Previous abbreviations for the virus were EBOV-Z (for Ebola virus Zaire) and ZEBOV (for Zaire Ebola virus or Zaire ebolavirus). In 2011, the ICTV explicitly rejected a proposal (2010.010bV) to recognize this name, as ICTV does not designate names for subtypes, variants, strains, or other subspecies level groupings. At present, ICTV does not officially recognize "Ebola virus" as a taxonomic rank, and rather continues to use and recommend only the species designation Zaire ebolavirus.

The prototype Ebola virus, variant Mayinga (EBOV/May), was named for Mayinga N'Seka, a nurse who died during the 1976 Zaire outbreak.

The disease typically occurs in outbreaks in tropical regions of Sub-Saharan Africa. From 1976 (when it was first identified) through 2013, the World Health Organization reported 1,716 confirmed cases. The largest outbreak to date is the ongoing 2014 West Africa Ebola virus outbreak, which is affecting Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia and Nigeria. As of 9 November 2014, 14,098 suspected cases and 5,489 deaths had been reported.

1976 Sudan outbreak

The first known outbreak of EVD was identified only after the fact, occurring between June and November 1976 in Nzara, South Sudan, (then part of Sudan) and was caused by Sudan virus (SUDV). The Sudan outbreak infected 284 people and killed 151. The first identifiable case in Sudan occurred on 27 June in a storekeeper in a cotton factory in Nzara, who was hospitalized on 30 June and died on 6 July. While the WHO medical staff involved in the Sudan outbreak were aware that they were dealing with a heretofore unknown disease, the actual "positive identification" process and the naming of the virus did not occur until some months later in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.Zaire outbreak

See also: Yambuku § Ebola outbreak

On 26 August 1976, a second outbreak of EVD began in Yambuku, a small rural village in Mongala District in northern Zaire (now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo). This outbreak was caused by EBOV, formerly designated Zaire ebolavirus, which is a different member of the genus Ebolavirus than in the first Sudan outbreak. The first person infected with the disease was village school headmaster Mabalo Lokela, who began displaying symptoms on 26 August 1976. Lokela had returned from a trip to Northern Zaire near the Central African Republic border, having visited the Ebola River between 12 and 22 August. He was originally believed to have malaria and was given quinine.

However, his symptoms continued to worsen, and he was admitted to

Yambuku Mission Hospital on 5 September. Lokela died on 8 September, 14

days after he began displaying symptoms.Soon after Lokela's death, others who had been in contact with him also died, and people in the village of Yambuku began to panic. This led the country's Minister of Health along with Zaire President Mobutu Sese Seko to declare the entire region, including Yambuku and the country's capital, Kinshasa, a quarantine zone. No one was permitted to enter or leave the area, with roads, waterways, and airfields placed under martial law. Schools, businesses and social organizations were closed. Researchers from the CDC, including Peter Piot, co-discoverer of Ebola, later arrived to assess the effects of the outbreak, observing that "the whole region was in panic." Piot concluded that the Belgian nuns had inadvertently started the epidemic by giving unnecessary vitamin injections to pregnant women, without sterilizing the syringes and needles. The outbreak lasted 26 days, with the quarantine lasting 2 weeks. Among the reasons that researchers speculated caused the disease to disappear, were the precautions taken by locals, the quarantine of the area, and discontinuing the injections.

During this outbreak, Dr. Ngoy Mushola recorded the first clinical description of EVD in Yambuku, where he wrote the following in his daily log: "The illness is characterized with a high temperature of about 39 °C (102 °F), hematemesis, diarrhea with blood, retrosternal abdominal pain, prostration with "heavy" articulations, and rapid evolution death after a mean of 3 days."

The virus responsible for the initial outbreak, first thought to be Marburg virus, was later identified as a new type of virus related to marburgviruses. Virus strain samples isolated from both outbreaks were named as the "Ebola virus" after the Ebola River, located near the originally identified viral outbreak site in Zaire. Reports conflict about who initially coined the name: either Karl Johnson of the American CDC team or Belgian researchers. Subsequently a number of other cases were reported, almost all centered on the Yambuku mission hospital or having close contact with another case. 318 cases and 280 deaths (a 88 percent fatality rate) occurred in Zaire. Although it was assumed that the two outbreaks were connected, scientists later realized that they were caused by two distinct ebolaviruses, SUDV and EBOV The Zaire outbreak was contained with the help of the World Health Organization and transport from the Congolese air force, by quarantining villagers, sterilizing medical equipment, and providing protective clothing.

1995 to 2012

The second major outbreak occurred in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) in 1995, affecting 315 and killing 254.In 2000, Uganda had an outbreak affecting 425 and killing 224; in this case the Sudan virus was found to be the Ebola species responsible for the outbreak.

In 2003 there was an outbreak in the Republic of the Congo that affected 143 and killed 128, a death rate of 90 percent, the highest death rate of a genus Ebolavirus outbreak to date.

In 2004 a Russian scientist died from Ebola after sticking herself with an infected needle.

Between April and August 2007, a fever epidemic in a four-village region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo was confirmed in September to have cases of Ebola. Many people who attended the recent funeral of a local village chief died. The 2007 outbreak eventually affected 264 individuals and resulted in the deaths of 187.

On 30 November 2007, the Uganda Ministry of Health confirmed an outbreak of Ebola in the Bundibugyo District in Western Uganda. After confirmation of samples tested by the United States National Reference Laboratories and the Centers for Disease Control, the World Health Organization confirmed the presence of a new species of genus Ebolavirus, which was tentatively named Bundibugyo. The WHO reported 149 cases of this new strain and 37 of those led to deaths.

The WHO confirmed two small outbreaks in Uganda in 2012. The first outbreak affected 7 people and resulted in the death of 4 and the second affected 24, resulting in the death of 17. The Sudan variant was responsible for both outbreaks.

On 17 August 2012, the Ministry of Health of the Democratic Republic of the Congo reported an outbreak of the Ebola-Bundibugyo variant in the eastern region. Other than its discovery in 2007, this was the only time that this variant has been identified as responsible for an outbreak. The WHO revealed that the virus had sickened 57 people and claimed 29 lives. The probable cause of the outbreak was tainted bush meat hunted by local villagers around the towns of Isiro and Viadana.

2013 to 2014 West African outbreak

Increase over time in the cases and deaths during the 2013–2014 outbreak

On 8 August 2014, the WHO declared the epidemic to be an international public health emergency. Urging the world to offer aid to the affected regions, the Director-General said, "Countries affected to date simply do not have the capacity to manage an outbreak of this size and complexity on their own. I urge the international community to provide this support on the most urgent basis possible." By mid-August 2014, Doctors Without Borders reported the situation in Liberia's capital Monrovia as "catastrophic" and "deteriorating daily". They reported that fears of Ebola among staff members and patients had shut down much of the city’s health system, leaving many people without treatment for other conditions. By late August 2014, the disease had spread to Nigeria, and one case was reported in Senegal. On 30 September 2014, the first confirmed case of Ebola in the United States was diagnosed. The patient died 8 days later.

Aside from the human cost, the outbreak has severely eroded the economies of the affected countries. A Financial Times report suggested the economic impact of the outbreak could kill more people than the virus itself. As of 23 September, in the three hardest hit countries, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, only 893 treatment beds were available even though the current need was 2122 beds. In a 26 September statement, the WHO said, "The Ebola epidemic ravaging parts of West Africa is the most severe acute public health emergency seen in modern times. Never before in recorded history has a biosafety level four pathogen infected so many people so quickly, over such a broad geographical area, for so long." The WHO reported that by 25 August more than 216 health-care workers were among the dead, partly due to the lack of equipment and long hours. On 23 October, the Malian government confirmed its first case. In response, UNMEER, in cooperation with the Logistics Cluster, air-lifted 1,050 kg of personal protective equipment (PPE) and body bags from Monrovia to Mali. As of 9 November 2014, 14,098 suspected cases and 5,489 deaths had been reported; however, the WHO has said that these numbers may be vastly underestimated.

2014 DRC Congo outbreak

An outbreak in Boende District in Equatorial Province was stopped effectively with flexible organization and funding, as well as social mobilization led by UNICEF advising action people could use. The DRC outbreak was from a local Ebola strain and not the one from West Africa (WHO).

2014 spread outside of Africa

Main articles: Ebola virus disease in the United States and Ebola virus disease in Spain

As of 15 October 2014, there have been 17 cases of Ebola treated outside of Africa, four of whom have died.

In early October, Teresa Romero, a 44-year-old Spanish nurse,

contracted Ebola after caring for a priest who had been repatriated from

West Africa. This was the first transmission of the virus to occur

outside of Africa.

On 20 October, it was announced that Teresa Romero had tested negative

for the Ebola virus, suggesting that she may have recovered from Ebola

infection.On 19 September, Eric Duncan flew from his native Liberia to Texas; 5 days later he began showing symptoms and visited a hospital, but was sent home. His condition worsened and he returned to the hospital on 28 September, where he died on 8 October. Health officials confirmed a diagnosis of Ebola on 30 September—the first case in the United States. On 12 October, the CDC confirmed that a nurse in Texas who had treated Duncan was found to be positive for the Ebola virus, the first known case of the disease to be contracted in the United States. On 15 October, a second Texas health-care worker who had treated Duncan was confirmed to have the virus. They have both recovered.

On 23 October, a doctor in New York City, who returned to the United States from Guinea after working with Doctors Without Borders, tested positive for Ebola. His case is unrelated to the Texas cases.

References

- "Ebola haemorrhagic fever in Zaire, 1976". Bull. World Health Organ. 56 (2): 271–93. 1978. PMC 2395567. PMID 307456.

- "Outbreak of Ebola Viral Hemorrhagic Fever – Zaire, 1995". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 44 (19): 381–2. 1995.

- "Ebola". Academic Kids.

- Elezra M. "Ebola: The Truth Behind The Outbreak (Video) l". Mabalo Lokela Archives – Political Mol.

- Ebola (1st ed.). New York: Rosen Pub. 2011. pp. 31, 52. ISBN 978-1435894334.

- Piot P, Marshall R (2012). No time to lose: a life in pursuit of deadly viruses (1st ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Co. pp. 30, 90. ISBN 978-0393063165.

- Peter Piot (11 August 2014). "Part one: A virologist's tale of Africa's first encounter with Ebola". ScienceInsider.Free access

- Peter Piot (13 August 2014). "Part two: A virologist's tale of Africa's first encounter with Ebola". ScienceInsider.Free access

- Bardi, Jason Socrates. "Death Called a River". The Scripps Research Institute. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- Preston, Richard (20 July 1995). The Hot Zone. Anchor Books (Random House). p. 117. "Karl Johnson named it Ebola"

- Bredow, Rafaela von; Hackenbroch, Veronika (4 October 2014). "'In 1976 I Discovered Ebola – Now I Fear an Unimaginable Tragedy'". The Observer. Guardian Media Group.

- King JW (2 April 2008). "Ebola Virus". eMedicine. WebMD. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- Formenty P, Libama F, Epelboin A, Allarangar Y, Leroy E, Moudzeo H, Tarangonia P, Molamou A, Lenzi M, Ait-Ikhlef K, Hewlett B, Roth C, Grein T (2003). "[Outbreak of Ebola hemorrhagic fever in the Republic of the Congo, 2003: a new strategy?]". Med Trop (Mars) (in French) 63 (3): 291–5. PMID 14579469.

- "Russian Scientist Dies in Ebola Accident at Former Weapons Lab". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- "Ebola outbreak in Congo". CBC.ca. CBC/Radio-Canada. 12 September 2007.

- "A Phase 1 Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo Controlled, Dose-Escalation Study to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of Prime-Boost VSV Ebola Vaccine in Healthy Adults". US NIAID. 9 Oct 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- Hannah Thibedeau (19 Oct 2014). "Ebola vaccine to be sent to WHO on Monday for clinical trials". CBC News. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- (1) Close, William T. (1995). Ebola: A Documentary Novel of Its First Explosion. New York: Ivy Books. ISBN 0804114323. OCLC 32753758. At Google Books.

(2) Grove, Ryan (2006-06-02). "More about the people than the virus". Review of Close, William T., Ebola: A Documentary Novel of Its First Explosion. Amazon.com. Retrieved 2014-09-17.

(3) Close, William T. (2002). Ebola: Through the Eyes of the People. Marbleton, Wyoming: Meadowlark Springs Productions. ISBN 0970337116. OCLC 49193962. At Google Books.

(4) Pink, Brenda (2008-06-24). "A fascinating perspective". Review of Close, William T., Ebola: Through the Eyes of the People. Amazon.com. Retrieved 2014-09-17. - (1) Clancy, Tom (1996). Executive Orders. New York: Putnam. ISBN 0399142185. OCLC 34878804. At Google Books.

(2) Line, Matt; Jeremy; Dan. "Executive Orders book reviews". AllReaders.com. Archived from the original on 2014-08-01. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

(3) Stone, Oliver (1996-09-02). "Who's That in the Oval Office?". Books News & Reviews. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on 2009-04-10.

I was diagnosed as HEPATITIS B carrier in 2013 with fibrosis of the

ReplyDeleteliver already present. I started on antiviral medications which

reduced the viral load initially. After a couple of years the virus

became resistant. I started on HEPATITIS B Herbal treatment from

ULTIMATE LIFE CLINIC (www.ultimatelifeclinic.com) in March, 2020. Their

treatment totally reversed the virus. I did another blood test after

the 6 months long treatment and tested negative to the virus. Amazing

treatment! This treatment is a breakthrough for all HBV carriers.