ebola virus cause & Transmission

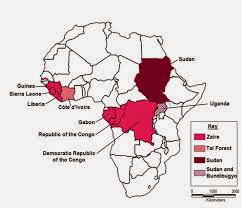

EVD in humans is caused by four of five viruses of the genus Ebolavirus. The four are Bundibugyo virus (BDBV), Sudan virus (SUDV), Taï Forest virus (TAFV) and one simply called Ebola virus (EBOV, formerly Zaire Ebola virus). EBOV, species Zaire ebolavirus, is the most dangerous of the known EVD-causing viruses, and is responsible for the largest number of outbreaks. The fifth virus, Reston virus (RESTV), is not thought to cause disease in humans, but has caused disease in other primates. All five viruses are closely related to marburgviruses.

The Ebola virus may be able to persist for up to 7 weeks in the semen of survivors after they recovered, which could lead to infections via sexual intercourse. Ebola may also occur in the breast milk of women after recovery, and it is not known when it is safe to breastfeed again. Otherwise, people who have recovered are not infectious.

The potential for widespread infections in countries with medical systems capable of observing correct medical isolation procedures is considered low. Usually when someone has symptoms of the disease, they are unable to travel without assistance.

Dead bodies remain infectious; thus, people handling human remains in practices such as traditional burial rituals or more modern processes such as embalming are at risk. 60% of the cases of Ebola infections in Guinea during the 2014 outbreak are believed to have been contracted via unprotected (or unsuitably protected) contact with infected corpses during certain Guinean burial rituals.

Health-care workers treating those who are infected are at greatest risk of getting infected themselves. The risk increases when these workers do not have appropriate protective clothing such as masks, gowns, gloves and eye protection; do not wear it properly; or handle contaminated clothing incorrectly. This risk is particularly common in parts of Africa where health systems function poorly and where the disease mostly occurs. Hospital-acquired transmission has also occurred in some African countries resulting from the reuse of needles. Some health-care centers caring for people with the disease do not have running water. In the United States the spread to two medial workers treating an infected patients prompted criticism of inadequate training and procedures.

Human to human transmission of EBOV through the air has not been reported to occur during EVD outbreaks and airborne transmission has only been demonstrated in very strict laboratory conditions in non-human primates. The apparent lack of airborne transmission among humans may be due to levels of the virus in the lungs that are insufficient to cause new infections. Spread of EBOV by water or food, other than bushmeat, has also not been observed. No spread by mosquitos or other insects has been reported.

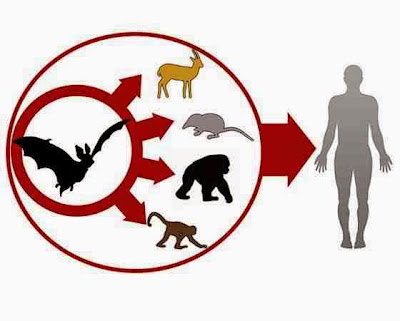

Although it is not entirely clear how Ebola initially spreads from animals to humans, the spread is believed to involve direct contact with an infected wild animal or fruit bat. Besides bats, other wild animals sometimes infected with EBOV include several monkey species, chimpanzees, gorillas, baboons and duikers.

Animals may become infected when they eat fruit partially eaten by bats carrying the virus. Fruit production, animal behavior and other factors may trigger outbreaks among animal populations.

Evidence indicates that both domestic dogs and pigs can also be infected with EBOV. Dogs do not appear to develop symptoms when they carry the virus, and pigs appear to be able to transmit the virus to at least some primates. Although some dogs in an area in which a human outbreak occurred had antibodies to EBOV, it is unclear whether they played a role in spreading the disease to people.

The natural reservoir for Ebola has yet to be confirmed; however, bats are considered to be the most likely candidate species. Three types of fruit bats (Hypsignathus monstrosus, Epomops franqueti and Myonycteris torquata) were found to possibly carry the virus without getting sick. As of 2013, whether other animals are involved in its spread is not known. Plants, arthropods and birds have also been considered possible viral reservoirs.

Bats were known to roost in the cotton factory in which the first cases of the 1976 and 1979 outbreaks were observed, and they have also been implicated in Marburg virus infections in 1975 and 1980. Of 24 plant and 19 vertebrate species experimentally inoculated with EBOV, only bats became infected. The bats displayed no clinical signs of disease, which is considered evidence that these bats are a reservoir species of EBOV. In a 2002–2003 survey of 1,030 animals including 679 bats from Gabon and the Republic of the Congo, 13 fruit bats were found to contain EBOV RNA. Antibodies against Zaire and Reston viruses have been found in fruit bats in Bangladesh, suggesting that these bats are also potential hosts of the virus and that the filoviruses are present in Asia.

Between 1976 and 1998, in 30,000 mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and arthropods sampled from regions of EBOV outbreaks, no Ebola virus was detected apart from some genetic traces found in six rodents (belonging to the species Mus setulosus and Praomys) and one shrew (Sylvisorex ollula) collected from the Central African Republic. However, further research efforts have not confirmed rodents as a reservoir. Traces of EBOV were detected in the carcasses of gorillas and chimpanzees during outbreaks in 2001 and 2003, which later became the source of human infections. However, the high rates of death in these species resulting from EBOV infection make it unlikely that these species represent a natural reservoir for the virus.

It is thought that fruit bats of the Pteropodidae family are natural Ebola virus hosts. Ebola is introduced into the human population through close contact with the blood, secretions, organs or other bodily fluids of infected animals such as chimpanzees, gorillas, fruit bats, monkeys, forest antelope and porcupines found ill or dead or in the rainforest.

Ebola then spreads through human-to-human transmission via direct contact (through broken skin or mucous membranes) with the blood, secretions, organs or other bodily fluids of infected people, and with surfaces and materials (e.g. bedding, clothing) contaminated with these fluids.

Health-care workers have frequently been infected while treating patients with suspected or confirmed EVD. This has occurred through close contact with patients when infection control precautions are not strictly practiced.

Burial ceremonies in which mourners have direct contact with the body of the deceased person can also play a role in the transmission of Ebola.

People remain infectious as long as their blood and body fluids, including semen and breast milk, contain the virus. Men who have recovered from the disease can still transmit the virus through their semen for up to 7 weeks after recovery from illness.

References

- Bardi, Jason Socrates. "Death Called a River". The Scripps Research Institute. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- "Ebola death toll tops 4,000 - WHO". http://indiarocks.co.in. http://Indiarocks.co.in. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- Gina Kolata (Oct 30, 2014). "Genes Influence How Mice React to Ebola, Study Says in ‘Significant Advance’". New York Times. Retrieved Oct 30, 2014.

- Angela L. Rasmussen with 21 others (Oct 30, 2014). "Host genetic diversity enables Ebola hemorrhagic fever pathogenesis and resistance". Science (journal). doi:10.1126/science.1259595. Retrieved Oct 30, 2014.

- http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-28262541

- Johnson, K. M.; Webb, P. A.; Lange, J. V.; Murphy, F. A. (1977). "Isolation and partial characterisation of a new virus causing haemorrhagic fever in Zambia". Lancet 309 (8011): 569–71. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92000-1. PMID 65661.

- Netesov, S. V.; Feldmann, H.; Jahrling, P. B.; Klenk, H. D.; Sanchez, A. (2000). "Family Filoviridae". In van Regenmortel, M. H. V.; Fauquet, C. M.; Bishop, D. H. L.; Carstens, E. B.; Estes, M. K.; Lemon, S. M.; Maniloff, J.; Mayo, M. A.; McGeoch, D. J.; Pringle, C. R.; Wickner, R. B. Virus Taxonomy—Seventh Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego, USA: Academic Press. pp. 539–48. ISBN 0-12-370200-3{{inconsistent citations}}

- Pringle, C. R. (1998). "Virus taxonomy-San Diego 1998". Archives of Virology 143 (7): 1449–59. doi:10.1007/s007050050389. PMID 9742051.

- Feldmann, H.; Geisbert, T. W.; Jahrling, P. B.; Klenk, H.-D.; Netesov, S. V.; Peters, C. J.; Sanchez, A.; Swanepoel, R.; Volchkov, V. E. (2005). "Family Filoviridae". In Fauquet, C. M.; Mayo, M. A.; Maniloff, J.; Desselberger, U.; Ball, L. A. Virus Taxonomy—Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego, USA: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 645–653. ISBN 0-12-370200-3.

- Mayo, M. A. (2002). "ICTV at the Paris ICV: results of the plenary session and the binomial ballot". Archives of Virology 147 (11): 2254–60. doi:10.1007/s007050200052.

- "Replace the species name Lake Victoria marburgvirus with Marburg marburgvirus in the genus Marburgvirus".

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. "Virus Taxonomy: 2013 Release".

- Wahl-Jensen, V.; Kurz, S. K.; Hazelton, P. R.; Schnittler, H.-J.; Stroher, U.; Burton, D. R.; Feldmann, H. (2005). "Role of Ebola Virus Secreted Glycoproteins and Virus-Like Particles in Activation of Human Macrophages". Journal of Virology 79 (4): 2413. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.4.2413-2419.2005. PMID 15681442.

- Kesel, A. J.; Huang, Z; Murray, M. G.; Prichard, M. N.; Caboni, L; Nevin, D. K.; Fayne, D; Lloyd, D. G.; Detorio, M. A.; Schinazi, R. F. (2014). "Retinazone inhibits certain blood-borne human viruses including Ebola virus Zaire". Antiviral Chemistry and Chemotherapy 23 (5): 197–215. doi:10.3851/IMP2568. PMID 23636868.

- Richardson JS, Dekker JD, Croyle MA, Kobinger GP (June 2010). "Recent advances in Ebolavirus vaccine development". Human Vaccines (open access) 6 (6): 439–49. doi:10.4161/hv.6.6.11097. PMID 20671437.

- "Statement on the WHO Consultation on potential Ebola therapies and vaccines". WHO. 5 September 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- "2014 Ebola Outbreakin West Africa". Retrieved Oct 2014.

- Alison P. Galvani with three others (21 August 2014). "Ebola Vaccination: If Not Now, When?". Annals of Internal Medicine. doi:10.7326/M14-1904.

0 comments:

Post a Comment